I recently got back to collecting books and I stumbled upon some pictures online. The pictures were for a couple of Romanian sci-fi magazines from the communist era. And then I remembered.

I was probably 12 years old (so maybe 2002?), back in my village where I had no access to cable TV (was getting only the national television, and, if lucky and wasn’t raining, the sister/back-up channel that was only running replay’s from the main channel). I was financially unfortunate (a.k.a fucking poor), and books were my only source of entertainment. I was reading pretty much anything, but mainly books from before ’89, because that’s what my old neighbors and the local library had. Interwar period literature, Greek myths, folktales, agriculture, mechanics, welding, you name it.

You wanna know how to grow a vineyard or how to repair an industrial harvester’s engine? What about listing the names of the Olympian gods? I gotchu!

But, it was also the time I got around both Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires, translated in Romanian at the now defunct publisher Ion Creangă and the Collection of Science-Fiction Stories (Colecția „Povestiri științifico-fantastice”). While I was fully aware of the former’s backstory, I didn’t know much about the latter. I was never big on SF, but I enjoyed it as much as the next guy. I didn’t even know it was a collection, but I figured that out when I noticed each issue was numbered.

I didn’t think much of it at the time. I knew the stories were old, from a bygone era. The magazines were thin, smelled like rat piss and they gave this pro-USSR propaganda vibe. However, I was enjoying reading those, and even staring sometimes at their vibrant cover illustrations. Whatever copies I “owned” weren’t many (courtesy to the village library, thank you very much!), and honestly, I never tried to find other issues. And, as time passed, I completely forgot about them all together.

Until these last few days. It was enough to see that picture on Google to unleash a full research on the internet to get to download the full collection in e-book version, and maybe, just maybe, see if the illustrations they had on the covers were as mind-blowing as I remembered them in my head. And boy, I wasn’t disappointed!

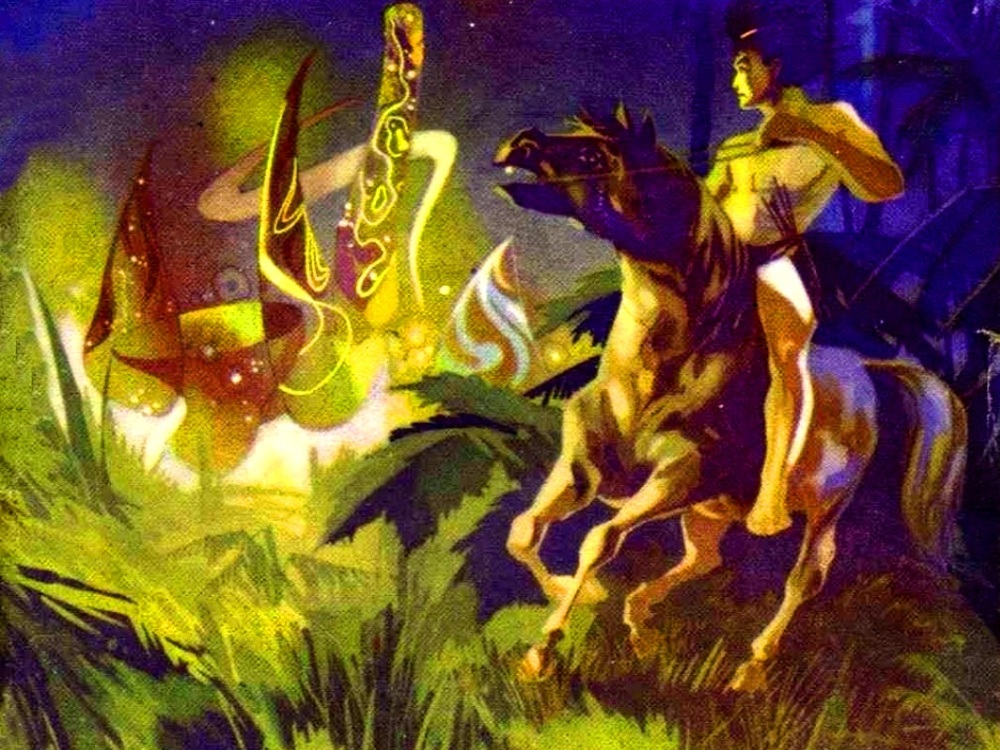

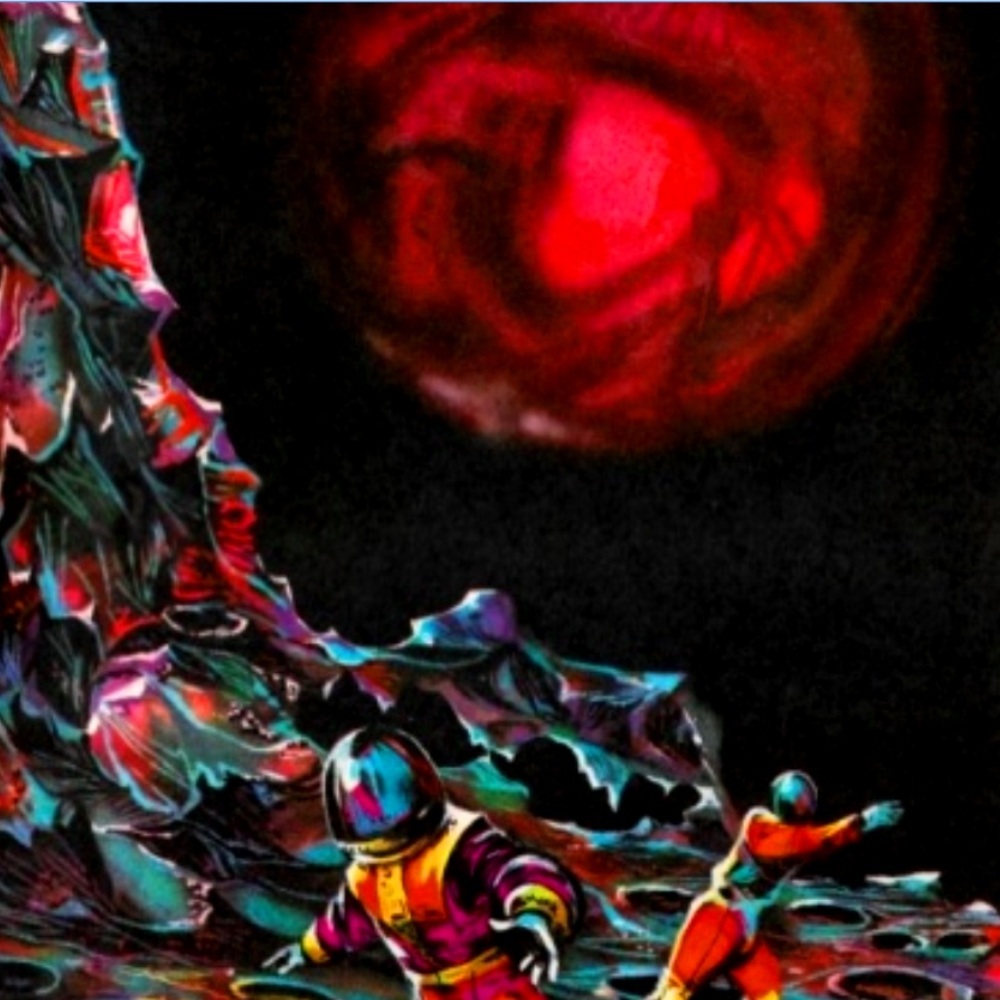

I found pretty much everything I was expecting. At first I found the e-books on a dedicated forum, carefully curated by an amateur CPSF fan club. And second, I found the covers, in poor quality, true, but enough to satisfy my newborn obsession. From minimalistic and abstract illustrations, to out-of-this-world sceneries and mind-bending, full blown psychedelic drawings that would make the art directors of the Foundation TV series cry for their mom.

Some of the drawings are heavily influenced by the soviet space dystopia, but some others are outstanding proof of incredible scientific imagination. Perhaps even sketches that are straight up opium fueled, beautifully embedded existential nightmares. But nevertheless, as I believe the illustrators never got the recognition they deserved, I thought I’d write this article.

Have a look at some of the works of artists such as Dumitru Ionescu, Aurel Buiculescu and Victor Wegemann, to name a few of the most prolific illustrators (pardon the poor photo quality):

First number of CPSF, as it came to be known, was published on October 1st 1955 as a result of a stories contest ran by the Science and Technology, and it was sold as a supplement to the actual magazine, probably to boost the sales and to spark to young generation’s interest for science. On the 1st issue’s 1st page one can read that “the main purpose of this collection is to cultivate among the readers the love for science, the bravery and the perseverance needed for every big achievement”. We’re all wheels and gears in this Motherland machine, kids!

Although barely noticeable at the beginning (the stories were written by local, fairly unknown authors or were simple translations of works by classics such as Verne, Stevenson, Poe), the magazine had to pay some tribute to the Party, in a form or another, to continue its existence. And so, from later numbers we can see some pretty clear signs of political connotation.

However, the amount and the quality of work done by contributing writers, translators and illustrators under the careful supervision of the resilient chief-editor Adrian Rogoz was massive, and respectable for that period. Within a span of almost two decades, 466 issues of CPSF were published. The magazine was the first of its kind, at least in Europe. Fun fact: Stanislaw Lem published the ground-breaking Solaris in 1961, and it was translated in Romanian by Rogoz at CPSF in 1967, with 4 years before the first translation in English. The phenomenon caught such a momentum that new and well established authors from all over the world (Japan, Iran, USA, Italy, Germany – both RFG and GDR, USSR, Czechoslovakia) were sending constant contributions. The first 80 issues were even translated in Hungarian as Tudományos-fantasztikus elbeszélések.

Although its original publication ceased in 1974, the magazine was renewed as CPSF Anticipatia in 1990, after the ’89 Revolution. Nowadays a series CPSF by Nemira is currently being published, carrying the torch further.

Source: Wiki | Photo: Anticariatul SF and Club CPSF’s e-books

Latest posts by Daniel Alexander (see all)

- IXV’s ‘Soundtracks for Crime Scenes’: The Musical Enigma of a Cold Case - April 21, 2024

- Bones and Butterflies: A Tribute to Fallen Creatures by Raluca Mihalcea - March 18, 2024

- Of Daggers and Guns: Maria Artene’s Time-Frozen Photography - November 16, 2023